Death

Cookies in the Staff Kitchen

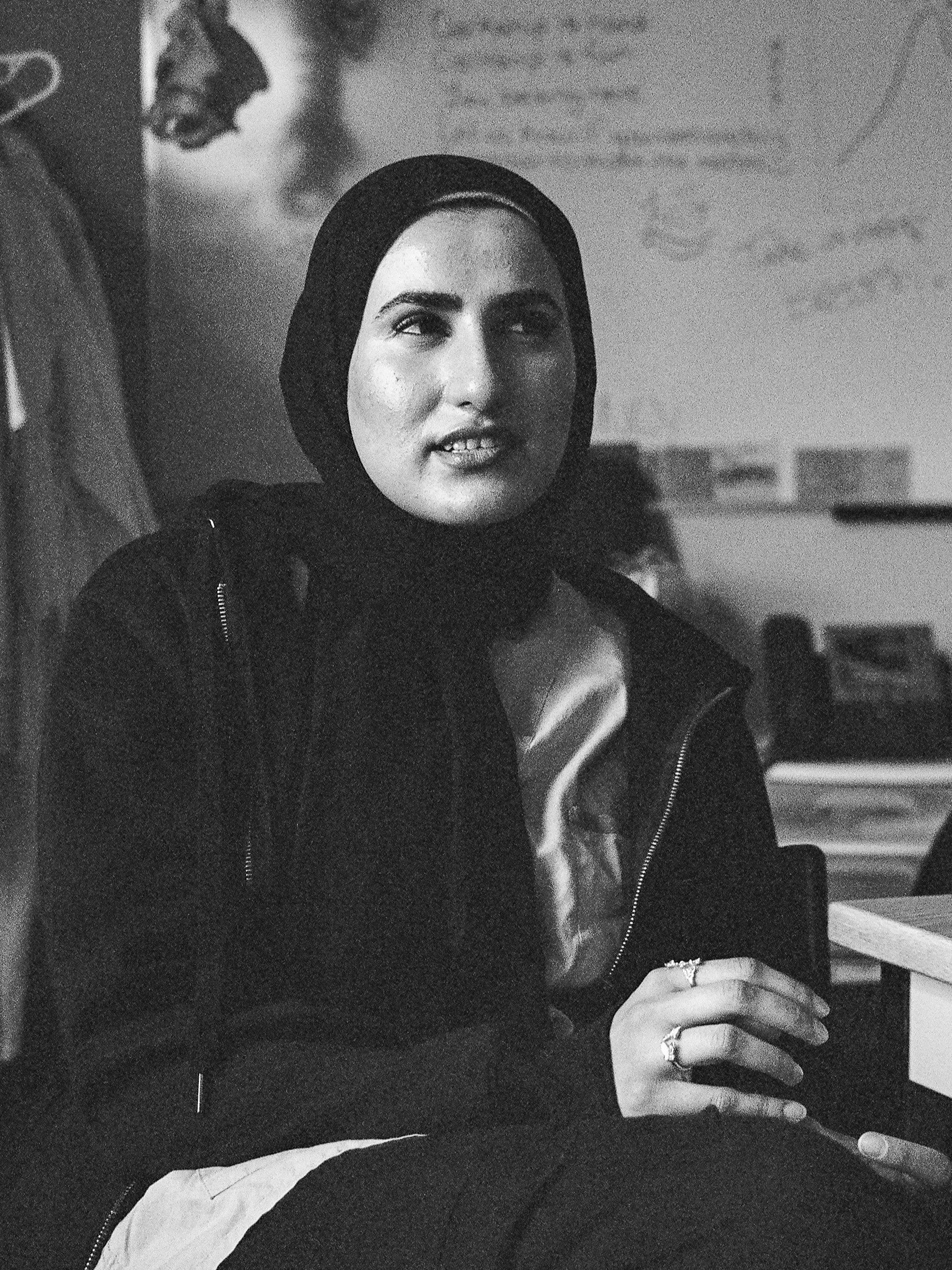

“If we’re grieving someone, that means that there was a connection there.”

I'll tell you about my first patient death. This patient was in their late 30s or early 40s.

I met them in clinic at the beginning of my time in [training site] and then again when they were admitted to the wards while I was doing inpatient rounds. I got to spend five days with them when they were in-hospital. They were in the ICU, and we could see that they were getting worse based on oxygen requirements and the fact that they had needed repeated hospitalizations. One cool thing was that we got a new doctor who had come to us from the SIPPA program. They were an internist previously and helped figure out some new aspects of therapy for this patient that literally no one was thinking about doing. It was something related to pulmonary rehabilitation, which was really cool to see. It really meant something to me that, just by coincidence, I saw this patient one month apart. They remembered my name, which was huge, and we could pick up where we left off—both in terms of medical things but also just life. A week after that second time that I met them, I heard some of the nurses talking about them in emerg. The patient had unfortunately died in hospital, but it wasn't a code? I guess the nurses hadn't checked in on them in a little while, and this patient wasn't on monitors, so no one noticed that they had passed. Everything was per norm for their care, so it was just surprising when they were found.

[Both Erin and Interviewer laugh because of the way that sentence came out]

It was a bummer. I'm laughing. You gotta laugh. That was the first time I heard about it as a medical student. After that event, I noticed that as I got to know many other patients longitudinally who also passed by nature, I started becoming accustomed to patient death which I think is a strength. I also gravitated towards palliative patients, so I did get more exposure to death.

There was one patient in his 80s who had super advanced dementia. His daughter was a huge, huge care provider for him. It was almost her role in life. She was very very tender with her dad. The first appointment where I met her was in clinic. Her dad couldn’t hear very well so she had a hearing thing where there was a mic attached to his hearing aids. She asked me to speak into the mic so he could hear properly. Then she pulled the doctor and me aside and was like, “I want to protect his feelings when we talk about the prognosis of his dementia.” She was just so protective. He ended up in hospital because he was having some dysphasia, I think. He had a palliative course and did eventually pass.

I saw his daughter afterwards, and I think there was a lot of trauma there. For five years, she had stopped her work, and her primary role had been to care for her dad. She was, first of all, grieving her dad, which I can't even imagine. Second of all, she now has to figure out what she’s going to do in life. She was probably just in her 40s. She was white, and it makes me think of how in Western culture, care homes are the norm, but that dynamic might not exist in other cultures. That was something for me to interrogate myself on. Will I do that for my parents as someone who is planning on always working? When I pull it all back to care for my parents, I actually don't know what I would prioritize. It makes me think about how that was a huge sacrifice for her, that I think only benefited her dad. Although he wasn’t able to communicate that to her verbally, I'm sure she felt it.

Those are all very different scenarios that you saw patients die. How did they affect you?

I think they affected me differently. For the first patient, it felt a bit like a tragedy because it was very unexpected for me. It being the first time that my patient died, and to hear about it in such a cavalier way and then to not be able to debrief it with anyone, it was all kinds of shock and a swirl of emotions. Whereas for some of my other patients, it was expected. There were already cookies in the staff kitchen from the family thanking us for their care. That felt like there had been a formal process that had already occurred.

You talked about the role of families, and probably saw a spectrum of involvement. We see grief from death, but there are also those cases where family members are relieved that someone died because they get their inheritance or something along those lines. Have you encountered anything like that?

I don’t think I have. I do remember one patient who coded in hospital, and unfortunately, the resuscitation was not successful. We called the family, and there was a lot of grief from them. I think the person who probably felt some relief may have been the woman who was the primary caregiver for the patient, whether she realized it or not. I feel like that was a huge weight off her shoulders, but then there was probably a lot of guilt with that.

What's one lesson from all of these deaths that's going to guide your future practice?

The idea of diagnosing something is very intimidating to me. That's a huge amount of leadership. I know I'm a good leader because I was on the exec for the [major] Student Association, but this is way different. We are going to be in charge of people's lives, and so decision paralysis is not an option.

One of the key themes I can pull from all of these is the uncertainty around death. There's always the chance that something could change in their trajectory. Practically speaking, we should have goals of care discussions with everyone coming into hospital so that we have some idea of what they would want. The other thing is remembering people are surrounded by a community, so that when one person dies, regardless of whether they have an obvious support system in the hospital, there will be someone who will grieve. That could be the daughter or a partner. It could be people at home we didn’t see or the med student who took care of them. My philosophy of grief is that if we're grieving someone, that means that there was a connection there, which I think is really special.

More Conversations in TCL